Mathematical Foundations

This chapter describes the mathematical foundations on which kafe2 is built, in particular the method of maximum likelihood and how confidence intervals are determined from the profile likelihood.

When performing a fit (as a physicist) the problem is as follows: you have some amount of measurement data from an experiment that you need to compare to one or more models to figure out which of the models - if any - provides the most accurate description of physical reality. You typically also want to know the values of the parameters of a model and the degree of (un)certainty on those values.

For very simple problems you can figure this out analytically: you take a formula and simply plug in your measurements. However, as your problems become more complex this approach becomes much more difficult - or even straight up impossible. For this reason complex problems are typically solved numerically: you use an algorithm to calculate a result that only approximates the analytical solution but in a way that is much easier to solve. kafe2 is a tool for the latter approach.

Cost Functions

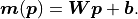

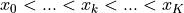

In the context of parameter estimation, a model  (where

(where  is just some index) is a function of the parameters

is just some index) is a function of the parameters  .

During the fitting process the parameters

.

During the fitting process the parameters  are varied in such a way that the

agreement between the model and the corresponding data

are varied in such a way that the

agreement between the model and the corresponding data  becomes “best”.

This of course means that we need to somehow define “good” or “bad” agreement - we need a metric.

This metric is called a loss function or cost function.

It is defined in such a way that a lower cost function value corresponds with a “better” agreement

between a model and our data.

becomes “best”.

This of course means that we need to somehow define “good” or “bad” agreement - we need a metric.

This metric is called a loss function or cost function.

It is defined in such a way that a lower cost function value corresponds with a “better” agreement

between a model and our data.

The cost functions implemented by kafe2 are based on the method of maximum likelihood.

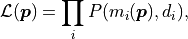

The idea behind this method is to maximize the likelihood function  which represents the probability with which a model

which represents the probability with which a model

would result in the data

would result in the data  that we ended up measuring:

that we ended up measuring:

where  describes the probability of measuring the data

point

describes the probability of measuring the data

point  given the corresponding model prediction

given the corresponding model prediction  .

This approach allows for a statistical interpretation of our fit results as we will see later.

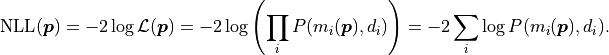

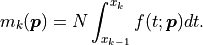

Instead of the likelihood described above however, we are instead using twice its negative

logarithm, the so-called negative log-likelihood (NLL):

.

This approach allows for a statistical interpretation of our fit results as we will see later.

Instead of the likelihood described above however, we are instead using twice its negative

logarithm, the so-called negative log-likelihood (NLL):

This transformation is allowed because logarithms are

strictly monotonically increasing functions, and therefore the negative logarithm of any

function will have its global minimum at the same place where the original function is maximal.

The model  that minimizes the NLL

will therefore also maximize the likelihood.

that minimizes the NLL

will therefore also maximize the likelihood.

While the above transformation may seem nonsensical at first, there are important advantages to calculating the negative log-likelihood over the likelihood:

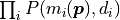

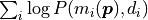

The product of the probabilities

is replaced by a

sum over the logarithms of the probabilities

is replaced by a

sum over the logarithms of the probabilities  .

In the context of a computer program sums are preferable over products because they can be

calculated more quickly and because a product of many small numbers can lead to

arithmetic underflow.

.

In the context of a computer program sums are preferable over products because they can be

calculated more quickly and because a product of many small numbers can lead to

arithmetic underflow.Because the probabilities

oftentimes contain exponential functions,

calculating their logarithm is actually faster because it reduces the number of necessary

operations.

oftentimes contain exponential functions,

calculating their logarithm is actually faster because it reduces the number of necessary

operations.Algorithms for numerical optimization minimize functions so they can be directly used to optimize the NLL.

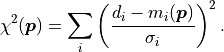

As an example, let us consider the likelihood function of data  that follows a

normal distribution around means

that follows a

normal distribution around means  with standard deviations (uncertainties)

with standard deviations (uncertainties)  :

:

![\mathcal{L}

= \prod_i P(\mu_i, \sigma_i, d_i)

= \prod_i \frac{1}{\sqrt[]{2 \pi} \: \sigma_i}

\exp \left[ - \frac{1}{2} \left( \frac{d_i - \mu_i}{\sigma_i} \right)^2 \right].](../_images/math/ee4d1135b2a8ca937e96117a86a8922ed4bffdf7.png)

The immediate trouble that we run into with this definition is that we have no idea what the

means  are - after all these are the “true values” that our data deviates from.

However, since we are trying to determine the likelihood with which our data would be produced

given our model we can set

are - after all these are the “true values” that our data deviates from.

However, since we are trying to determine the likelihood with which our data would be produced

given our model we can set  .

.

Note

Conceptually uncertainties are typically associated with the data  even though

they represent deviations from the model

even though

they represent deviations from the model  .

However, because the normal distribution is symmetric this does not have an effect on the

likelihood function

.

However, because the normal distribution is symmetric this does not have an effect on the

likelihood function  (as long as the uncertainties

(as long as the uncertainties  do not depend on the model

do not depend on the model

).

).

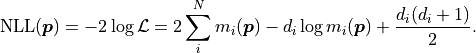

For the NLL we now find:

![\mathrm{NLL}(\bm{p})

= -2 \log \mathcal{L}({\bm p}) \\

= - 2 \log \prod_i \frac{1}{\sqrt[]{2 \pi} \: \sigma_i}

\exp \left[ - \frac{1}{2} \left( \frac{d_i - m_i({\bm p})}{\sigma_i} \right)^2 \right] \\

= - 2 \sum_i \log \frac{1}{\sqrt[]{2 \pi} \: \sigma_i}

+ \sum_i \left( \frac{d_i - m_i({\bm p})}{\sigma_i} \right)^2 \\

=: - 2 \log L_\mathrm{max} + \chi^2({\bm p}) .](../_images/math/64198e2d2cff8f14a01a7b269089c7b6c423b622.png)

As we can see the logarithm cancels out the exponential function of the normal

distribution and we are left with two parts:

The first is a part represented by  that only depends on the

uncertainties

that only depends on the

uncertainties  but not on the model

but not on the model  or the data

or the data  .

This is the minimum value the NLL could possibly take on if the model

.

This is the minimum value the NLL could possibly take on if the model  were to exactly fit the data

were to exactly fit the data  .

The second part can be summed up as

.

The second part can be summed up as

As mentioned before, this is much easier and faster to calculate than the original

likelihood function.

If the uncertainties  are constant we can ignore the first part and directly use

are constant we can ignore the first part and directly use

(chi-squared) as our cost function because

we are only interested in differences between cost function values.

This special case of the method of maximum likelihood is known as the method of least squares

and it is by far the most common cost function used for fits.

(chi-squared) as our cost function because

we are only interested in differences between cost function values.

This special case of the method of maximum likelihood is known as the method of least squares

and it is by far the most common cost function used for fits.

Covariance

The  cost function that we discussed in the previous section assumes

that our data points

cost function that we discussed in the previous section assumes

that our data points  are subject to uncertainties

are subject to uncertainties  .

With this notation we implicitly assumed that our uncertainties are independent of one another:

that there is no relationship between the uncertainties of any two individual data points.

Independent uncertainties are frequently caused by random fluctuations in the measurement values,

either because of technical limitations of the experimental setup (electronic noise, mechanical

vibrations) or because of the intrinsic statistical nature of the measured observable (as is typical

in quantum mechanics, e. g. radioactive decays).

.

With this notation we implicitly assumed that our uncertainties are independent of one another:

that there is no relationship between the uncertainties of any two individual data points.

Independent uncertainties are frequently caused by random fluctuations in the measurement values,

either because of technical limitations of the experimental setup (electronic noise, mechanical

vibrations) or because of the intrinsic statistical nature of the measured observable (as is typical

in quantum mechanics, e. g. radioactive decays).

However, there are also correlated uncertainties that arise due to effects that distort multiple measurements in the same way. Such uncertainties can for example be caused by a random imperfection of the measurement device which affects all measurements equally. The uncertainties of the measurements taken with such a device are no longer uncorrelated, but instead have one common uncertainty.

Historically uncertainties have been divided into statistical and systematic uncertainties.

While this is appropriate when propagating the uncertainties of the input variables by hand it is

not a suitable distinction for a numerical fit.

In kafe2 multiple uncertainties are combined to construct a so-called covariance matrix.

This is a matrix with the pointwise data variances  on its diagonal and the covariances

on its diagonal and the covariances  between two data points outside the diagonal.

By using this covariance matrix for our fit we can estimate the uncertainty of our model parameters

numerically with no need for propagating uncertainties by hand.

between two data points outside the diagonal.

By using this covariance matrix for our fit we can estimate the uncertainty of our model parameters

numerically with no need for propagating uncertainties by hand.

As mentioned before, the diagonal elements of our covariance matrix represent the variances

of our data points.

They simply represent the uncertainty of a single data point

of our data points.

They simply represent the uncertainty of a single data point  while ignoring all other

data points.

An element outside the diagonal at position

while ignoring all other

data points.

An element outside the diagonal at position  represents the covariance

represents the covariance

between points

between points  and

and  :

:

![\mathrm{Cov}_{ij}

= E[ (d_i - E[d_i])(d_j - E[d_j]) ]

= E[d_i \cdot d_j] - E[d_i] \cdot E[d_j],](../_images/math/5b8116a0dbdcceb08478db7635ab7e3bec12131a.png)

where  is the expected value of a variable.

The covariance

is the expected value of a variable.

The covariance  is a measure of the joint variability of

is a measure of the joint variability of  and

and

- but for a meaningful interpretation it needs to be considered relative to the

pointwise uncertainties

- but for a meaningful interpretation it needs to be considered relative to the

pointwise uncertainties  .

We therefore define the so-called Pearson correlation coefficient

.

We therefore define the so-called Pearson correlation coefficient  as follows:

as follows:

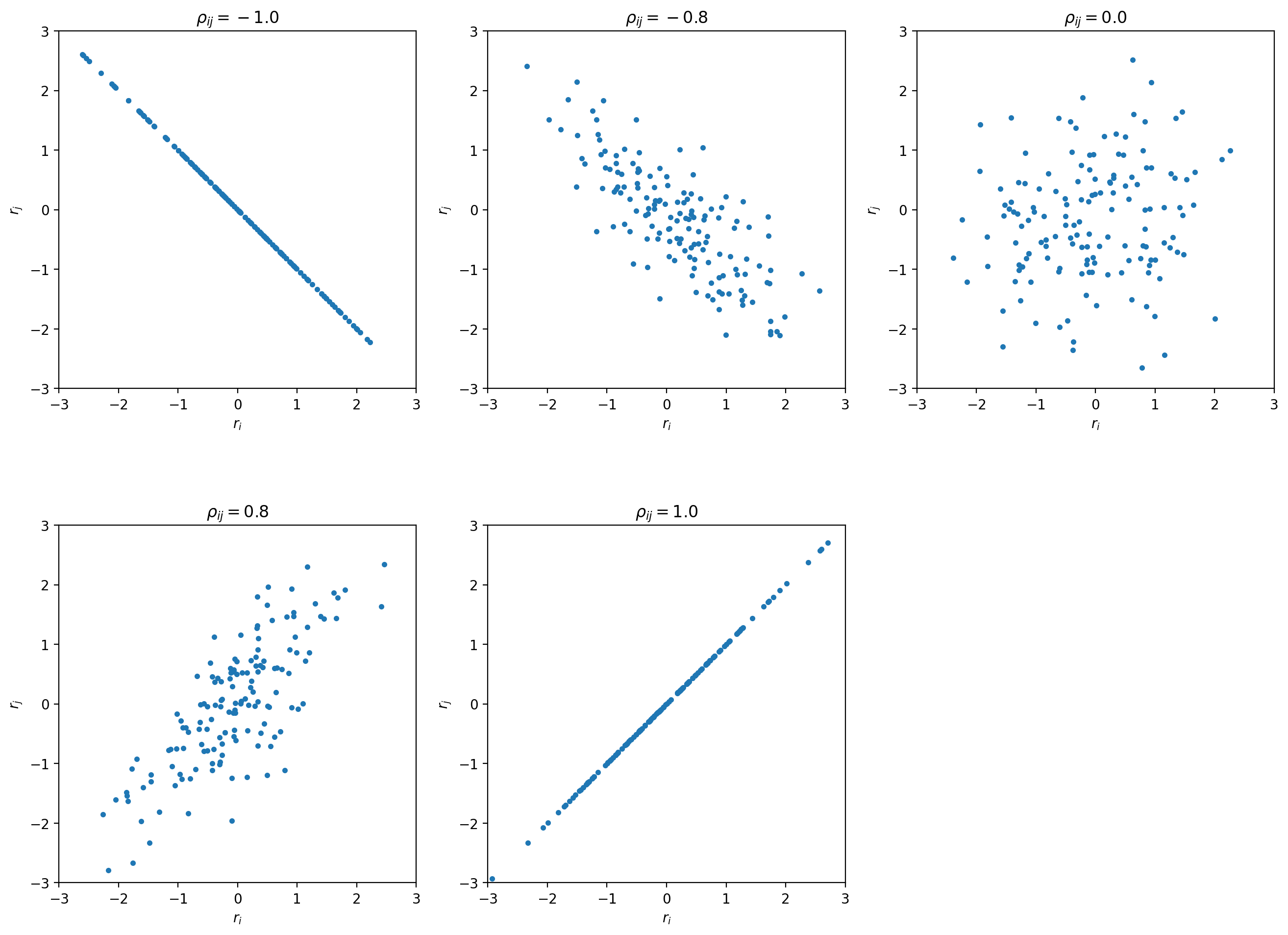

The correlation  is normalized to the interval

is normalized to the interval ![[-1, 1]](../_images/math/92b4b754966e4a581f924d4bfd1b0db7ab47c886.png) .

Its absolute value is a measure of how strongly the residuals

.

Its absolute value is a measure of how strongly the residuals  depend on one another.

In other words, the absolute value of

depend on one another.

In other words, the absolute value of  measures how much information

you get about

measures how much information

you get about  or

or  if you know the other one.

For

if you know the other one.

For  they are completely independent from one another.

For

they are completely independent from one another.

For

and

and  are directly proportional to one

another with a positive (negative) proportional constant for

are directly proportional to one

another with a positive (negative) proportional constant for

(

( ).

Let’s look at some toy samples for different values of

).

Let’s look at some toy samples for different values of  :

:

For  the sample forms a circle around (0,0).

As the absolute value of

the sample forms a circle around (0,0).

As the absolute value of  increases the sample changes its shape to a tilted

ellipse - some combinations of

increases the sample changes its shape to a tilted

ellipse - some combinations of  and

and  become more likely than others.

For

become more likely than others.

For  the ellipse becomes a line -

in this degenerate case we really only have one source of uncertainty that affects two data points.

the ellipse becomes a line -

in this degenerate case we really only have one source of uncertainty that affects two data points.

Covariance Matrix Construction

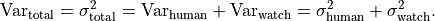

In a physics experiment it is typically necessary to consider more than one source of uncertainty.

Let us consider the following example:

we want to measure Earth’s gravitational constant  by dropping things from various heights

and timing the time they take to hit the ground with a stopwatch.

We assume an independent uncertainty of

by dropping things from various heights

and timing the time they take to hit the ground with a stopwatch.

We assume an independent uncertainty of  for each data point

because humans are not able to precisely align pressing the button of a stopwatch with the actual

event.

For one reason or another the stopwatch we’re using is also consistently

off by a few percentage points.

To account for this we assume a fully correlated (

for each data point

because humans are not able to precisely align pressing the button of a stopwatch with the actual

event.

For one reason or another the stopwatch we’re using is also consistently

off by a few percentage points.

To account for this we assume a fully correlated ( ) uncertainty of

) uncertainty of

for all data points.

To determine the variance of a single data point we can simply add up the variances

of the uncertainty sources:

for all data points.

To determine the variance of a single data point we can simply add up the variances

of the uncertainty sources:

As it turns out we can use the same approach for the covariances: we can simply add up the covariance matrices of the different uncertainty sources to calculate a total covariance matrix:

The next question would then be how you would determine the covariance matrices for the

individual uncertainty sources.

A useful approach is to split a covariance matrix into a vector of uncertainty  and the corresponding correlation matrix

and the corresponding correlation matrix  :

:

where  is the Hadamard product (a.k.a. Schur product).

In other words, the components of

is the Hadamard product (a.k.a. Schur product).

In other words, the components of  are calculated by simply multiplying the

components of

are calculated by simply multiplying the

components of  and

and  at

the same position.

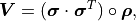

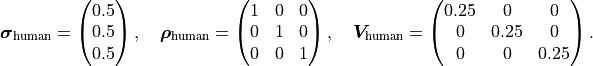

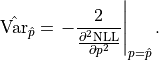

If we assume that we have three data points we can express the human uncertainty as follows:

at

the same position.

If we assume that we have three data points we can express the human uncertainty as follows:

Because the human uncertainties of the individual data points are completely independent from one

another the covariance/correlation matrix is a diagonal matrix.

On the other hand, given some data points  the watch uncertainty is expressed like this:

the watch uncertainty is expressed like this:

Because the watch uncertainties of the individual data points are fully correlated all components of the correlation matrix are equal to 1. However, this does not necessarily mean that all components of the covariance matrix are also equal. In this example the watch uncertainty per data point is relative, meaning that the absolute uncertainty differs from data point to data point.

If we were to visualize the correlations of the uncertainty components described above, we would find that samples of the human component form a circle while samples from the watch component form a line. If we were to visualize the total uncertainty we would end up with the mixed case where the sample forms an ellipse.

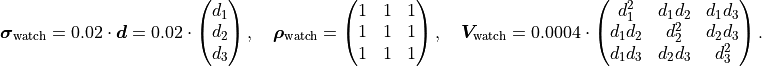

Parameter Confidence Intervals

When we perform a fit we are not only interested in the parameter values that fit our data “best”,

we also want to determine the uncertainty on our result.

The standard method with which fitting tools determine parameter confidence intervals is to make

use of the so-called Rao-Cramér-Fréchet bound.

It states for the variance of the estimator of a single parameter estimate  :

:

![\mathrm{Var}_{\hat{p}} \ge 2 \frac{1 + \frac{\partial b}{\partial p}}

{E \left[ \frac{\partial^2 \mathrm{NLL}}{\partial p^2} \right]},](../_images/math/15648e9d1e71019ed37fe5896b8a5decbc72a325.png)

where  is the bias of the estimator.

Because the bias cannot be easily computed it is usually assumed to be 0 in practice

(check with a Monte Carlo study when in doubt).

Furthermore, because likelihood methods are efficient (if an efficient estimator exists at all)

the uncertainties on the fit results decrease “quickly” as more data is added and the RCF bound

becomes an equality.

Finally, in the large sample limit (i.e. if you have “enough” data and your uncertainties are

sufficiently small) the expectation in the

denominator can be replaced with the derivative of the likelihood at the cost function minimum.

All together we thus find for the uncertainty of our fit result:

is the bias of the estimator.

Because the bias cannot be easily computed it is usually assumed to be 0 in practice

(check with a Monte Carlo study when in doubt).

Furthermore, because likelihood methods are efficient (if an efficient estimator exists at all)

the uncertainties on the fit results decrease “quickly” as more data is added and the RCF bound

becomes an equality.

Finally, in the large sample limit (i.e. if you have “enough” data and your uncertainties are

sufficiently small) the expectation in the

denominator can be replaced with the derivative of the likelihood at the cost function minimum.

All together we thus find for the uncertainty of our fit result:

The default output of a fitting tool are  as the parameter value and

as the parameter value and

as the parameter error.

For reasons that will become clear in the following sections these errors will also be referred to

as the “parabolic errors”.

If the estimator

as the parameter error.

For reasons that will become clear in the following sections these errors will also be referred to

as the “parabolic errors”.

If the estimator  of a parameter is normally distributed then so-called

confidence intervals can be calculated which (for a random dataset) contain the true value

of a parameter is normally distributed then so-called

confidence intervals can be calculated which (for a random dataset) contain the true value

with a given probability called the confidence level

with a given probability called the confidence level  .

For a confidence interval

.

For a confidence interval  the confidence level is calculated by integrating the

probability density function of the normal distribution:

the confidence level is calculated by integrating the

probability density function of the normal distribution:

The confidence interval bounds are frequently chosen symmetrically around  and

expressed as multiples of

and

expressed as multiples of  .

For example, the “

.

For example, the “ interval”

interval”

has a confidence level

of approximately 68%.

has a confidence level

of approximately 68%.

If  is normally distributed then the method described above can be used directly.

In the large sample limit this is always the case for maximum likelihood estimators.

If you don’t have enough data (or if you don’t know) you will need to use e.g. the method described

in the next section.

is normally distributed then the method described above can be used directly.

In the large sample limit this is always the case for maximum likelihood estimators.

If you don’t have enough data (or if you don’t know) you will need to use e.g. the method described

in the next section.

Profile Likelihood (1 Parameter)

Let’s assume we have a fit with only a single parameter  .

If the estimator

.

If the estimator  is normally distributed then the negative log-likelihood

is normally distributed then the negative log-likelihood

is a parabola.

If

is a parabola.

If  is varied by

is varied by  standard deviations

standard deviations  from the

optimal value in either direction then

from the

optimal value in either direction then  increases by

increases by  .

For a non-Gaussian estimator the confidence intervals derived from the RCF bound can be approximated

by determining the parameter values at which

.

For a non-Gaussian estimator the confidence intervals derived from the RCF bound can be approximated

by determining the parameter values at which

is equal to the squared

equivalent sigma value

is equal to the squared

equivalent sigma value  .

In general the confidence intervals determined in this manner with this “profile likelihood method”

will be asymmetrical.

In loose terms, if the cost function value increases very sharply when we move away from the cost

function minimum then this tells us that even a small deviation from our fit result would result in

a significantly worse fit, making large deviations unlikely.

Conversely, if the cost function value increases very slowly when we move away

from the cost function minimum then this tells us that a deviation from our

fit result would result in a fit that is only slightly worse than our optimal fit result,

making such a deviation from our fit result quite possible.

.

In general the confidence intervals determined in this manner with this “profile likelihood method”

will be asymmetrical.

In loose terms, if the cost function value increases very sharply when we move away from the cost

function minimum then this tells us that even a small deviation from our fit result would result in

a significantly worse fit, making large deviations unlikely.

Conversely, if the cost function value increases very slowly when we move away

from the cost function minimum then this tells us that a deviation from our

fit result would result in a fit that is only slightly worse than our optimal fit result,

making such a deviation from our fit result quite possible.

The obvious problem with the profile likelihood method described above is that in practice fits

will almost always have more than one parameter

(the additional parameters being denoted as  ).

So how do we determine the values for these other parameters as we vary just one of them?

The solution is to choose

).

So how do we determine the values for these other parameters as we vary just one of them?

The solution is to choose  in such a

way that

in such a

way that  becomes minimal.

In practical terms this means that we fix

becomes minimal.

In practical terms this means that we fix  to several values near the cost function minimum

and then perform a fit over all other parameters for each of these values

(this process is called profiling).

In this context the parameters

to several values near the cost function minimum

and then perform a fit over all other parameters for each of these values

(this process is called profiling).

In this context the parameters  are called nuisance parameters:

we don’t care about their values (right now) but we need to include them in our fits for

a statistically correct result.

are called nuisance parameters:

we don’t care about their values (right now) but we need to include them in our fits for

a statistically correct result.

If the estimator  is normally distributed then the confidence intervals derived from

the profile likelihood are the same as the ones derived from the RCF bound - if you suspect that

this is not the case you should always check the profiles of the parameters.

The easiest way to do this is to set the flag

is normally distributed then the confidence intervals derived from

the profile likelihood are the same as the ones derived from the RCF bound - if you suspect that

this is not the case you should always check the profiles of the parameters.

The easiest way to do this is to set the flag profile = True when calling kafe2.xy_fit or

kafe2.plot.

The parabolic parameter uncertainties are then replaced with the edges of the

1- -intervals determined from the profile likelihood.

Because these intervals are not necessarily symmetric around the cost function minimum they are

referred to as asymmetric parameter errors in kafe2

(in Minuit they are called Minos errors).

-intervals determined from the profile likelihood.

Because these intervals are not necessarily symmetric around the cost function minimum they are

referred to as asymmetric parameter errors in kafe2

(in Minuit they are called Minos errors).

When the above flag is set kafe2 will then also create plots of the profile likelihood in

addition to the regular plots.

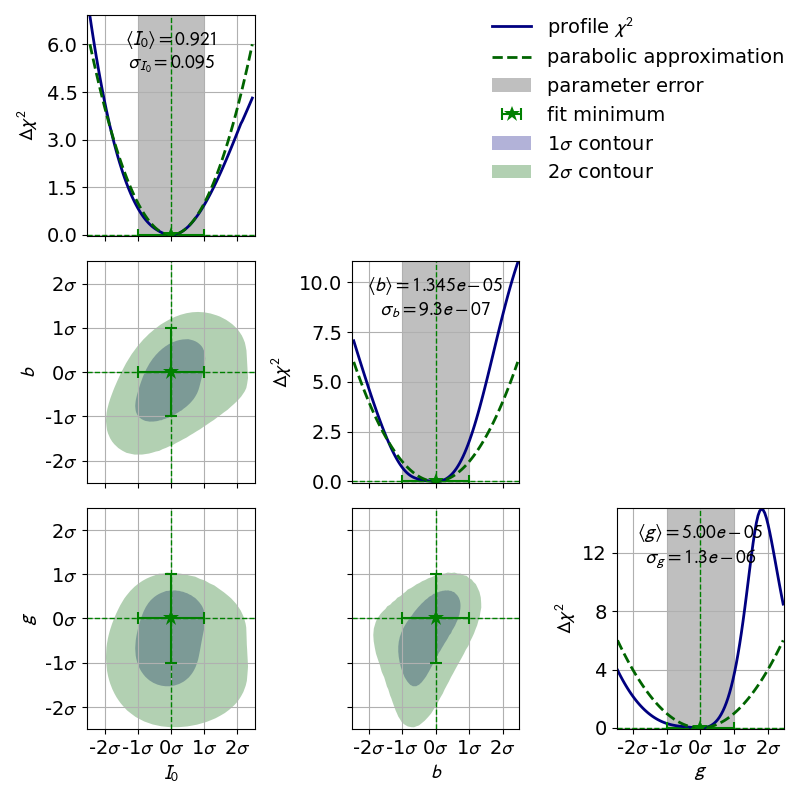

As an example, let us look at the profile of the parameter  from the double slit example:

from the double slit example:

The profile of this parameter is very clearly asymmetric and not even close to the parabolic approximation of a normal distribution. If we had only looked at the parabolic parameter error we could have unknowingly assumed confidence intervals that are very inaccurate.

Profile Likelihood (2 parameters)

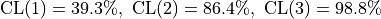

In the previous section we learned about the profiles of single fit parameters which serve as a replacement for the parabolic errors of single fit parameters. In this section we will learn about so-called contours, which serve as a replacement for the covariance of two fit parameters. Conceptually profiles and contours are very similar. A profile can be used to define confidence intervals for a single parameter with a certain probability of containing the true value of a parameter while a contour defines a confidence region with a certain probability of containing a pair of parameters. Let us start by looking at the contours produced in the double slit example:

In this visualization the confidence region inside the contours is colored.

By looking at the legend we find that the contours correspond to

1  and 2

and 2  .

Notably the confidence levels of the corresponding confidence regions are not

the same as in one dimension.

In one dimension 1

.

Notably the confidence levels of the corresponding confidence regions are not

the same as in one dimension.

In one dimension 1  corresponds to roughly 68% while

2

corresponds to roughly 68% while

2  corresponds to roughly 95%.

We could derive these confidence levels by integrating the probability density function

of the standard normal distribution over the interval

corresponds to roughly 95%.

We could derive these confidence levels by integrating the probability density function

of the standard normal distribution over the interval ![[-\sigma , \sigma]](../_images/math/56622cf23958e5f5950007cb52d6c6940b56c7ab.png) for a desired

for a desired  value.

In two dimensions we instead integrate the PDF of the uncorrelated standard bivariate

normal distribution over a circle with radius

value.

In two dimensions we instead integrate the PDF of the uncorrelated standard bivariate

normal distribution over a circle with radius  around the origin:

around the origin:

![\mathrm{CL}(\sigma)

= \int_0^\sigma dr \int_0^{2 \pi} d \varphi \ r \frac{1}{2 \pi} e^{- \frac{r^2}{2}}

= \int_0^\sigma dr \ r e^{- \frac{r^2}{2}}

= \left[ -e^{-\frac{r^2}{2}} \right]_0^\sigma

= 1 - e^{-\frac{\sigma^2}{2}}.](../_images/math/248f0c48b45b23ae885bc570c1b2d69b88190daa.png)

With this formula we now find

.

.

Note

So far there has been no mention of how a contour for a given

could be calculated.

This is because (efficiently) calculating these contours is not straightforward and

even in kafe2 this is an area of active development.

could be calculated.

This is because (efficiently) calculating these contours is not straightforward and

even in kafe2 this is an area of active development.

The parabolic equivalent of a contour is to look at the parameter covariance matrix and to extrapolate the correlated distribution of two estimators. As with the input uncertainties the confidence region calculated this way will always be an ellipse. For (nearly) normally distributed estimators such as the estimators from the exponential fit in the “model functions” example the calculated contours will then look something like this:

If the estimators were normally distributed the 1- -contour would reach exactly from

-contour would reach exactly from

to

to  while the 2-

while the 2- -contour would reach exactly from

-contour would reach exactly from  to

to  .

As we can see the deviation from this is very small so we can probably use the parameter covariance

matrix (or the parabolic parameter errors and the parameter correlation matrix) without issue.

If we require highly precise confidence intervals for our parameters

this might not be acceptable though.

.

As we can see the deviation from this is very small so we can probably use the parameter covariance

matrix (or the parabolic parameter errors and the parameter correlation matrix) without issue.

If we require highly precise confidence intervals for our parameters

this might not be acceptable though.

Note

The degree to which confidence intervals/regions are distorted from their parabolic approximation depends on the scale at which the profile likelihood is calculated. Because every function minimum can be accurately approximated by a parabola at infinitesimally small scales (Taylor expansion) the parabolic approximation becomes more accurate for small parameter uncertainties. Conversely, for large parameter uncertainties the parabolic approximation of the profile likelihood becomes less accurate.

Nonlinear Models

In the previous section we discussed the profile likelihood and how it can be used to calculate confidence intervals for our fit parameters. We also discussed how it is necessary to use this method if the parameter estimators are not normally distributed. What was not discussed is how to determine if an estimator is normally distributed in the first place. This is where this section comes in.

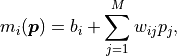

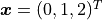

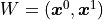

Linear Models

Let us assume we have some vector of  data points

data points  with corresponding

constant Gaussian uncertainties

with corresponding

constant Gaussian uncertainties  (that can also be correlated).

A linear model is then defined as a model

(that can also be correlated).

A linear model is then defined as a model

that is a multilinear function of its

that is a multilinear function of its  parameters

parameters  :

:

where the weights  and biases

and biases  are simply real numbers (the biases

here have nothing to do with the bias in the RCF bound).

Put another way, each model value

are simply real numbers (the biases

here have nothing to do with the bias in the RCF bound).

Put another way, each model value  is a linear combination of the

parameter values

is a linear combination of the

parameter values  plus some bias

plus some bias  .

We can express the same relationship as above with a weight matrix

.

We can express the same relationship as above with a weight matrix  and a bias vector

and a bias vector  :

:

If we now use the method of least squares ( ) to estimate the

optimal fit parameters

) to estimate the

optimal fit parameters  we get a very useful property:

the estimators of our parameters are normally distributed.

We can therefore skip the (relatively) expensive process of profiling the parameters!

we get a very useful property:

the estimators of our parameters are normally distributed.

We can therefore skip the (relatively) expensive process of profiling the parameters!

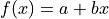

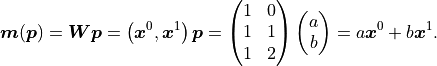

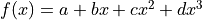

Let us look at some examples for linear models in the context of xy fits since

those are the most common.

Let us therefore assume that we have some y data  measured at

x values

measured at

x values  .

For our model function we choose the first degree polynomial

.

For our model function we choose the first degree polynomial  .

We can thus express our model like this:

.

We can thus express our model like this:

The upper indices of vectors are to be interpreted as powers of said vectors using the

Hadamard/Schur product (component-wise multiplication).

In the above equation we only have a weight matrix  but no bias vector.

We can clearly see that the first degree polynomial (a line) is a linear model.

Let’s take a look at the third degree polynomial

but no bias vector.

We can clearly see that the first degree polynomial (a line) is a linear model.

Let’s take a look at the third degree polynomial  :

:

Again we find that the model  is a linear function

of its parameters

is a linear function

of its parameters  .

A third degree polynomial is therefore also a linear model.

This is even though the model function is not a linear function

of the independent variable

.

A third degree polynomial is therefore also a linear model.

This is even though the model function is not a linear function

of the independent variable  .

However, this was never required in our definition of linear models to begin with because

.

However, this was never required in our definition of linear models to begin with because

is not one of our fit parameters.

In fact, all polynomials are linear models.

is not one of our fit parameters.

In fact, all polynomials are linear models.

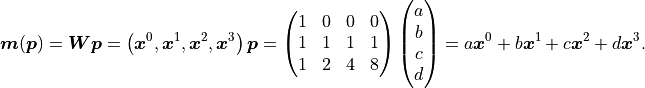

Nonlinear Models

Now that we have defined linear models, the definition of nonlinear models is

rather easy: a model that is not a linear model.

The natural consequence of this is that the estimators of our fit parameters are no longer

guaranteed to be normally distributed.

We will therefore need to resort to calculating confidence intervals from the profile likelihood.

Let us consider an exponential model as an example:  .

It is simply not possible to express this function using only a finite weight matrix

.

It is simply not possible to express this function using only a finite weight matrix  and a bias vector

and a bias vector  .

We would instead need an infinitely large matrix and infinitely many parameters.

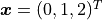

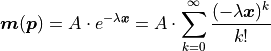

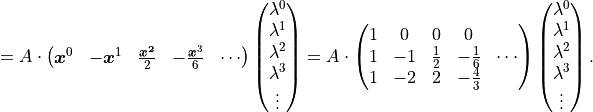

With the same x vector

.

We would instead need an infinitely large matrix and infinitely many parameters.

With the same x vector  as before we find:

as before we find:

Note

We could of course just cut off the series at some point to approximate the exponential function.

This would be equivalent to approximating the exponential function with a polynomial.

But this would not allow us to calculate an estimate for the parameter  - which is

very often the entire point of a physics experiment.

- which is

very often the entire point of a physics experiment.

Unfortunately, even with a linear model function the regression problem as a whole can become

nonlinear if certain kafe2 features are used.

As of right now these features are uncertainties in x direction for xy fits

and uncertainties relative to the model.

This is because when using those features the uncertainties that we feed to our

negative log-likelihood are no longer constant.

Instead they become a function of the fit parameters:  .

.

Another complication is that we then have to consider the full Gaussian likelihood rather

than just  to avoid biasing our results:

to avoid biasing our results:

![\mathrm{NLL}(\bm{p})

= - 2 \log L_\mathrm{max}(\bm p) + \chi^2({\bm p})

= - 2 \sum_i \log \frac{1}{\sqrt[]{2 \pi} \: \sigma_i(\bm{p})} + \chi^2(\bm{p}) \\

= N \log (2 \pi) + 2 \sum_i^N \log \sigma_i(\bm{p}) + \chi^2(\bm{p})

=: N \log (2 \pi) + C_\mathrm{det}(\bm{p}) + \chi^2(\bm{p}).](../_images/math/ea2349f36b7e87a49d97fc812593eee1d3a942e9.png)

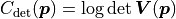

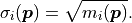

As with our derivation of  we end up with a constant term

we end up with a constant term  which we can ignore because we are only interested in the differences in cost.

We also get a new term

which we can ignore because we are only interested in the differences in cost.

We also get a new term  that

we need to consider when our uncertainties depend on our fit parameters.

The new term results in higher cost when the uncertainties increase.

If we didn’t add

that

we need to consider when our uncertainties depend on our fit parameters.

The new term results in higher cost when the uncertainties increase.

If we didn’t add  while handling parameter-dependent uncertainties

we would end up with a bias towards parameter values for which the uncertainties are increased

because those values result in a lower value for

while handling parameter-dependent uncertainties

we would end up with a bias towards parameter values for which the uncertainties are increased

because those values result in a lower value for  .

The subscript “det” is short for determinant, the reason for which should become clear when we

look at the full Gaussian likelihood with correlated uncertainties represented

by a covariance matrix

.

The subscript “det” is short for determinant, the reason for which should become clear when we

look at the full Gaussian likelihood with correlated uncertainties represented

by a covariance matrix  :

:

![\mathrm{NLL}(\bm{p})

= - 2 \log L_\mathrm{max}(\bm{p}) + \chi^2(\bm{p})

= - 2 \log \left[ (2 \pi)^{-\frac{N}{2}}

\frac{1}{\sqrt{\det \bm{V}(\bm{p})}} \right] + \chi^2(\bm{p}) \\

= N \log (2 \pi) + \log \det \bm{V}(\bm{p}) + \chi^2(\bm{p})

=: N \log (2 \pi) + C_\mathrm{det}(\bm{p}) + \chi^2(\bm{p})](../_images/math/39c82fa8c80b082c63d041e4ac0df7b42fbd5510.png)

The constant term is the same as with the uncorrelated uncertainties but term we’re interested in

has changed to  .

If the uncertainties are uncorrelated then the covariance matrix is diagonal

and the result is equal to the term we found earlier.

.

If the uncertainties are uncorrelated then the covariance matrix is diagonal

and the result is equal to the term we found earlier.

Note

Handling correlated uncertainties that are a function of our fit parameters

is computationally expensive because this means that we need to recalculate

the inverse (actually Cholesky decomposition) of our covariance many times which has

complexity

is computationally expensive because this means that we need to recalculate

the inverse (actually Cholesky decomposition) of our covariance many times which has

complexity  for

for  data points - on modern hardware

this is typically not an issue though.

data points - on modern hardware

this is typically not an issue though.

Uncertainties In x Direction

Now that we know how to handle parameter-dependent uncertainties we can use this knowledge

to handle a very common problem:

fitting a model with model function  to data with x values

to data with x values  and

uncertainties in both the x and the y direction.

The uncertainties in the y direction

and

uncertainties in both the x and the y direction.

The uncertainties in the y direction  can be used directly.

For the x uncertainties

can be used directly.

For the x uncertainties  we need a trick:

we project the uncertainties

we need a trick:

we project the uncertainties  onto the y axis by

multiplying them with the corresponding model function derivative by x

onto the y axis by

multiplying them with the corresponding model function derivative by x  :

:

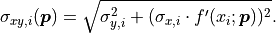

The formula for the pointwise projected xy uncertainties  can

be generalized for the equivalent covariance matrices

can

be generalized for the equivalent covariance matrices  and

and  :

:

where  is again the Hadamard product (a.k.a. Schur product) where two matrices

are multiplied on a component-by-component basis.

We are also implicitly assuming that

is again the Hadamard product (a.k.a. Schur product) where two matrices

are multiplied on a component-by-component basis.

We are also implicitly assuming that  is a vectorized function à la

NumPy that returns a vector of derivatives for a vector of x values

is a vectorized function à la

NumPy that returns a vector of derivatives for a vector of x values  .

.

Uncertainties Relative To The Model

Relative uncertainties are very common.

For example, the uncertainties of digital multimeters are

typically specified as a percentage of the reading.

Unfortunately such uncertainties are therefore relative to the true values which we don’t know.

The standard approach for handling relative uncertainties is therefore to specify them relative

to the data points  which we do know.

However, this approach introduces a bias:

if the random fluctuation represented by an uncertainty causes our data

which we do know.

However, this approach introduces a bias:

if the random fluctuation represented by an uncertainty causes our data  to have

a reduced (increased) absolute value

then the relative uncertainties are underestimated (overestimated).

This causes a bias towards models with smaller absolute values in our fit because we are giving

data points that randomly happen to have a low absolute value a higher weight than data points

with a high absolute value -

and this bias increases for large relative uncertainties.

to have

a reduced (increased) absolute value

then the relative uncertainties are underestimated (overestimated).

This causes a bias towards models with smaller absolute values in our fit because we are giving

data points that randomly happen to have a low absolute value a higher weight than data points

with a high absolute value -

and this bias increases for large relative uncertainties.

A better result can be achieved by specifying uncertainties relative to the model

rather than the data

rather than the data  .

Because the model (ideally) converges against the true values in the large sample limit we no longer

give a higher weight to data that randomly happens to have a lower absolute value.

The price we pay for this is that our total uncertainty becomes a function of our model parameters

.

Because the model (ideally) converges against the true values in the large sample limit we no longer

give a higher weight to data that randomly happens to have a lower absolute value.

The price we pay for this is that our total uncertainty becomes a function of our model parameters

which results in an increase in computation time as described above.

which results in an increase in computation time as described above.

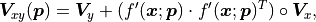

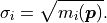

Gaussian Approximation Of The Poisson Distribution

kafe2 has a built-in approximation of the Poisson distribution where the Gaussian uncertainty is assumed as:

The rationale for using the square root of the model  rather than the square

root of the data

rather than the square

root of the data

is the same as with the relative uncertainties described in the previous section.

The benefit of using this approximation of the Poisson distribution instead of the

Poisson distribution itself is that it is capable of

handling additional Gaussian uncertainties on our data.

is the same as with the relative uncertainties described in the previous section.

The benefit of using this approximation of the Poisson distribution instead of the

Poisson distribution itself is that it is capable of

handling additional Gaussian uncertainties on our data.

Hypothesis Testing

So far we have used cost functions to compare how good or bad certain models

and parameter values fit our data relative to each other -

but we have never discussed how good or bad a fit is in an absolute sense.

Luckily for us there is a metric that we can use:

, where

, where  is simply the sum of the

squared residuals that we already know and

is simply the sum of the

squared residuals that we already know and  is the

number of degrees of freedom that our fit has.

The basic definition of

is the

number of degrees of freedom that our fit has.

The basic definition of  is that it’s simply the number

of data points

is that it’s simply the number

of data points  minus the number of parameters

minus the number of parameters  :

:

Conceptually the number of degrees of freedom are the number of “extra measurements”

over the minimum number of data points needed to fully specify a model with  linearly independent parameters.

If our model is not fully specified then our cost function has multiple

(or even infinitely many) global minima.

For example, a line with model function

linearly independent parameters.

If our model is not fully specified then our cost function has multiple

(or even infinitely many) global minima.

For example, a line with model function  has two

linearly independent parameters and as such needs at least two data points to be fully

specified.

has two

linearly independent parameters and as such needs at least two data points to be fully

specified.

If our model accurately describes our data, and if our assumptions about

the uncertainties of our data are correct, then  has an expected value of 1.

If

has an expected value of 1.

If  is smaller (larger) than 1 we might be

overestimating (underestimating) the uncertainties on our data.

If

is smaller (larger) than 1 we might be

overestimating (underestimating) the uncertainties on our data.

If  is much larger than 1 then our model may not

accurately describe our data at all.

is much larger than 1 then our model may not

accurately describe our data at all.

To further quantify these rather loose criteria we can make use of Pearson’s chi-squared test.

This is a statistical test that allows us to calculate the probability

with which we can expect to observe deviations from

our model that are at least as large as the deviations that we saw in our data.

To conduct this test we first need to define the so-called

with which we can expect to observe deviations from

our model that are at least as large as the deviations that we saw in our data.

To conduct this test we first need to define the so-called  distribution.

This distribution has a single parameter

distribution.

This distribution has a single parameter  and when sampling from this distribution,

the samples from

and when sampling from this distribution,

the samples from  standard normal distributions

standard normal distributions  are simply squared and then added up:

are simply squared and then added up:

The deviations of our data relative to its true values (represented by our model) and

normalized to its uncertainties follow such standard normal distributions.

We can therefore expect the sum of the squares of these deviations  to follow

a

to follow

a  distribution with

distribution with  -

if our model and our assumptions about the uncertainties of our data are correct.

We can associate the following cumulative distribution function (CDF)

-

if our model and our assumptions about the uncertainties of our data are correct.

We can associate the following cumulative distribution function (CDF)

with the

with the  distribution:

distribution:

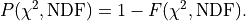

To calculate the probability  with which we would expect a

with which we would expect a

value larger than what we got for our fit

(i.e. the probability of our fit being worse if we were to repeat it with a new random dataset)

we can now simply use:

value larger than what we got for our fit

(i.e. the probability of our fit being worse if we were to repeat it with a new random dataset)

we can now simply use:

In kafe2  is also referred to as the

is also referred to as the  probability.

We can use this number to determine if deviations from our

assumed model are statistically significant.

probability.

We can use this number to determine if deviations from our

assumed model are statistically significant.

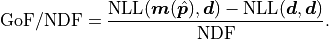

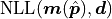

The concept of  as can be generalized for non-Gaussian likelihoods

where the metric becomes goodness of fit

per degree of freedom

as can be generalized for non-Gaussian likelihoods

where the metric becomes goodness of fit

per degree of freedom  .

For a negative log likelihood

.

For a negative log likelihood  with model

with model  and

data

and

data  it is defined like this:

it is defined like this:

We are subtracting the so-called saturated likelihood  (the minimum value our NLL could have if our model were to perfectly describe our data)

from the global cost function minimum

(the minimum value our NLL could have if our model were to perfectly describe our data)

from the global cost function minimum  and then divide this difference by

and then divide this difference by  .

As before the expected value of

.

As before the expected value of  is 1

if our model and our assumptions about the uncertainties of our data are correct.

is 1

if our model and our assumptions about the uncertainties of our data are correct.

Calculating Data Uncertainties from

Many fitting tools allow users to fit a model to data without specifying any data uncertainties.

This seems to be at odds with our current understanding of Gaussian likelihood-based fits where

we always required our data to have some amount of uncertainty.

So how does this work?

The “solution” is to first give all data points an uncorrelated uncertainty of 1 and to scale

these uncertainties after the fit in such a way that  is equal to 1.

This approach has a big problem which makes it unsuitable for physics experiments:

we cannot do any hypothesis tests because we are

implicitly assuming that our model is 100% correct.

This goes against the very purpose of many physics experiments where experimenters are trying to

determine if a theoretical model is consistent with experimental data.

is equal to 1.

This approach has a big problem which makes it unsuitable for physics experiments:

we cannot do any hypothesis tests because we are

implicitly assuming that our model is 100% correct.

This goes against the very purpose of many physics experiments where experimenters are trying to

determine if a theoretical model is consistent with experimental data.

For example, at the Large Hadron Collider the standard model of particle physics has undergone very thorough testing that continues to this day. So far, no statistically significant deviations from the standard model have been found - which is actually a bummer for theoretical physicists. You see, we know for a fact that the standard model is incomplete because (among other things) it does not include gravity. If we were to find an area in which the predictions of the standard model are incompatible with the measured data this would give theorists an important clue for a new theory that could potentially fix the problems of the standard model.

Fixing And Constraining Parameters

kafe2 allows users to fix fit parameters.

The practical consequence of this is that one of our fit parameters becomes a constant and

is not changed during the fit.

Because this effectively lowers the number of fit parameters we have to consider the number

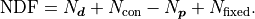

of fixed parameters  in the calculation of the number of degrees of fredom:

in the calculation of the number of degrees of fredom:

It’s also possible to constrain fit parameters.

Constraints are effectively direct measurements of our fit parameters and they

increase the cost of our fit if they are not exactly met.

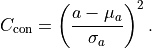

For example, the additional cost  of a Gaussian constraint for

fit parameter

of a Gaussian constraint for

fit parameter  with mean

with mean  and standard deviation

and standard deviation  can be calculated like this:

can be calculated like this:

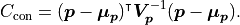

We can of course generalize this concept to account for correlations between

parameters  as defined by a covariance matrix

as defined by a covariance matrix  :

:

If we define any constraints we are adding more data to our fit.

We therefore also have to increase  by the number of constraints

by the number of constraints  :

:

A simple parameter constraint that constrains a single parameter counts as one constraint.

On the other hand, a matrix parameter constraint that constrains  parameters at once

counts as

parameters at once

counts as  constraints.

constraints.

Data/Fit Types

A large percentage of fits can be expressed as an XYFit.

However, there are cases where an XYFit is not suitable;

kafe2 offers alternatives fit types for those cases.

Typically these alternative fit types are associated with alternative data (container) types

so both concepts are explained simultaneously in this section.

For example, an XYFit uses an XYContainer to hold its xy data

while a HistFit uses a HistContainer to hold and bin its data.

For the following considerations  always describes the vector of fit parameters.

Unless mentioned otherwise fits calculate their cost from a data vector

always describes the vector of fit parameters.

Unless mentioned otherwise fits calculate their cost from a data vector  and a model vector

and a model vector  .

.

XYFit

Let’s start with the most common fit type: XYFit.

The data associated with this fit type consists of two vectors of equal length:

a vector of x data  and a vector of y data

and a vector of y data  .

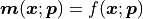

Our model values are calculated as

.

Our model values are calculated as  ,

they are a function of our x data and our fit parameters.

As the difference in notation implies the x and y axes are not treated in the same way.

The x axis is interpreted as the independent variable of our fit while the y data values

,

they are a function of our x data and our fit parameters.

As the difference in notation implies the x and y axes are not treated in the same way.

The x axis is interpreted as the independent variable of our fit while the y data values

and y model values

and y model values  are what we ultimately

compare to calculate the negative log-likelihood.

are what we ultimately

compare to calculate the negative log-likelihood.

Note

Although we only have a few discreet x values for which we have to calculate our model

, our model function

, our model function  is still expected to be a continuous function of

is still expected to be a continuous function of  .

.

A visualization of XYFit is fairly straightforward:

the xy axes of our fix directly correspond to the axes of a plot.

IndexedFit

Conceptually IndexedFit is a simplified version of XYFit:

we only have a data vector  and no independent variable at all.

Instead we calculate the model vector

and no independent variable at all.

Instead we calculate the model vector  as a function of just the fit parameters.

In kafe2

as a function of just the fit parameters.

In kafe2 IndexedFit is visualized by interpreting the indices of the data/model

vectors as x values and the corresponding xth entry of those vectors as the y value.

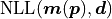

HistFit

HistFit handles  one-dimensional data points

one-dimensional data points  by binning them

according to some bin edges

by binning them

according to some bin edges  to form our data vector

to form our data vector

.

By default the model function

.

By default the model function  that is fitted to these bins is a

probability density function for the observed values

that is fitted to these bins is a

probability density function for the observed values  .

The bin heights

.

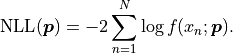

The bin heights  predicted by our model are obtained by integrating

predicted by our model are obtained by integrating

over a given bin and multiplying the result with

over a given bin and multiplying the result with  :

:

The amplitude of our distribution is therefore not one of the fit parameters;

we are effectively fitting a density function to a normalized histogram.

By setting density=False when creating the HistFit object an arbitrary model can

be fit to a histogram that is not normalized.

Unlike with XYFit or IndexedFit the default distribution assumed for the

data of a HistFit is the Poisson distribution rather than the normal distribution.

UnbinnedFit

Just like HistFit an UnbinnedFit accepts a vector of  one-dimensional data points

one-dimensional data points  in conjunction with a probability density function

in conjunction with a probability density function

for these values as its model function.

As the name implies the data is not binned.

Instead, because our model function can be interpreted as a probability density we can simply

calculate the negative log-likelihood like this:

for these values as its model function.

As the name implies the data is not binned.

Instead, because our model function can be interpreted as a probability density we can simply

calculate the negative log-likelihood like this:

In kafe2 UnbinnedFit is visualized by interpreting the independent variable as the

x axis of a plot and the height of the probability density function as the y axis.

Additionally, a thin, vertical line is added for each data point to indicate

the density of our data.

CustomFit

Unlike the other fit types discussed so far, CustomFit does not explicitly use data

or a model

or a model  .

Instead the user has to manually define how the cost function value is calculated from the fit

parameters

.

Instead the user has to manually define how the cost function value is calculated from the fit

parameters  .

Because any potential data is outside kafe2 there is no built-in visualization (plotting)

available except for the fit parameter profiles/contours calculated by

.

Because any potential data is outside kafe2 there is no built-in visualization (plotting)

available except for the fit parameter profiles/contours calculated by ContoursProfiler.

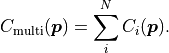

MultiFit

A MultiFit is constructed from  regular fits with cost functions

regular fits with cost functions

.

The idea behind

.

The idea behind MultiFit is rather simple:

multiple models that share at least one parameter are

simultaneously fitted to their respective data.

In accordance with the method of maximum likelihood the optimal fit parameters are those that make

the observed combination of individual datasets the most likely.

The corresponding cost function can simply be calculated as:

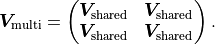

If a MultiFit is built from several fits that assume Gaussian uncertainties,

it’s possible to specify uncertainties that are correlated between those fits.

For example, in the case of two fits that have a fully correlated source of uncertainty expressed

by a covariance matrix  the effective covariance matrix

the effective covariance matrix

for the

for the MultiFit becomes:

Cost Functions

So far we almost universally assumed that the uncertainties of our data can be described with a normal distribution. However, this is not always the case. For example, the number of radioactive decays in a given time interval follows a Poisson distribution. In kafe2 such distinctions are handled via the cost function, the function that in one way or another calculates a scalar cost from the data, model, and uncertainties of a fit. This section describes the built-in cost functions that kafe2 provides.

Cost Function

Cost Function

The by far most common cost function used is the  cost function that assumes a normal

distribution for the uncertainties of our data.

In kafe2 the name is strictly speaking a misnomer because the actual cost calculation considers

the full likelihood rather than just

cost function that assumes a normal

distribution for the uncertainties of our data.

In kafe2 the name is strictly speaking a misnomer because the actual cost calculation considers

the full likelihood rather than just  in order to handle non-constant uncertainties.

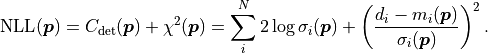

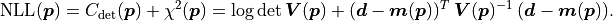

For

in order to handle non-constant uncertainties.

For  data points

data points  with corresponding model values

with corresponding model values  and uncorrelated (but possible non-constant) uncertainties

and uncorrelated (but possible non-constant) uncertainties  the cost function value is calculated like this:

the cost function value is calculated like this:

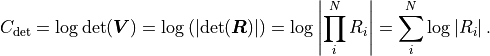

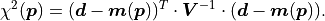

If the uncertainties are instead correlated as described by a covariance matrix

the cost function value becomes:

the cost function value becomes:

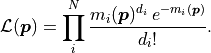

Poisson Cost Function

The Poisson cost function assumes - as the name implies - a Poisson distribution for our data.

Compared to the normal distribution the Poisson distribution has two important features:

Firstly the data values  (but not the model values

(but not the model values  )

have to be positive integers, and secondly the mean and variance are inherently linked.

We can define the likelihood function

)

have to be positive integers, and secondly the mean and variance are inherently linked.

We can define the likelihood function  of the Poisson distribution like this:

of the Poisson distribution like this:

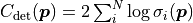

The negative log-likelihood  thus becomes:

thus becomes:

Notably  depends only on the data

depends only on the data  and the model

and the model

but not on any specified uncertainties

but not on any specified uncertainties  .

The advantage is that we don’t need to specify any uncertainties -

but the significant disadvantage is that we can’t specify any uncertainties either.

In such cases the cost function in the following section will need to be used.

.

The advantage is that we don’t need to specify any uncertainties -

but the significant disadvantage is that we can’t specify any uncertainties either.

In such cases the cost function in the following section will need to be used.

Gauss Approximation Cost Function

Because a Poisson distribution cannot handle Gaussian data uncertainties the Poisson distribution

is frequently approximated with a normal distribution.

The easiest approach is to simply derive the uncertainties  from the data

from the data  :

:

However, as described in the previous section about linear models,

this leads to a bias towards small model values  .

In kafe2 the uncertainties are therefore derived from the model values:

.

In kafe2 the uncertainties are therefore derived from the model values:

Just like before these uncertainties can be easily combined with other sources of uncertainty

by simply adding up the (co)variances.

However, this approach has an important limitation:

it is only valid if the model values  are large enough

(something like

are large enough

(something like  ).

This is because for small model values the asymmetry of the Poisson distribution and the portion

of the normal distribution that resides in the unphysical region with

).

This is because for small model values the asymmetry of the Poisson distribution and the portion

of the normal distribution that resides in the unphysical region with  are no longer negligible.

are no longer negligible.

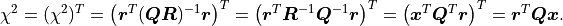

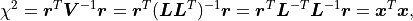

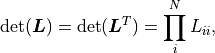

Numerical Considerations

The mathematical description of  shown so far makes use of the inverse of the

covariance matrix

shown so far makes use of the inverse of the

covariance matrix  .

However, kafe2 does not actually calculate

.

However, kafe2 does not actually calculate  .

Instead the so-called QR decomposition

.

Instead the so-called QR decomposition  of the covariance matrix is being

used where

of the covariance matrix is being

used where  is an orthogonal matrix and

is an orthogonal matrix and  is an upper triangular matrix.

Calculating

is an upper triangular matrix.

Calculating  is faster than calculating

is faster than calculating  and it also reduces

the rounding error from floating point operations.

and it also reduces

the rounding error from floating point operations.

Because  is a triangular matrix

solving

the corresponding system of linear equations for the residual vector

is a triangular matrix

solving

the corresponding system of linear equations for the residual vector

(difference between data and model) can be done very quickly:

(difference between data and model) can be done very quickly:

With  and

and  we now find:

we now find:

At the same time, because  is an orthogonal matrix its determinant is either

is an orthogonal matrix its determinant is either  or

or  .

.

is a triangular matrix and its determinant is simply the product of its diagonal values.

Valid covariance matrices have a positive determinant, so

is a triangular matrix and its determinant is simply the product of its diagonal values.

Valid covariance matrices have a positive determinant, so  can be efficiently calculated as:

can be efficiently calculated as:

Instead of a QR decomposition kafe2 can alternatively use a so-called Cholesky decomposition

with  where

where  is a lower triangular matrix.

The tradeoff is that a Cholesky decomposition is faster but less numerically stable than a QR decomposition.

Like with a QR decomposition the corresponding system of linear equations can be solved quickly:

is a lower triangular matrix.

The tradeoff is that a Cholesky decomposition is faster but less numerically stable than a QR decomposition.

Like with a QR decomposition the corresponding system of linear equations can be solved quickly:

and

and  can be calculated as:

can be calculated as:

instead of the pointwise uncertainties

instead of the pointwise uncertainties

with

with  .

.